Many founders ignore how VCs make money.

In my opinion, that's a mistake.

How will you convince a VC you will make them money if you don't know how they make money for themselves?

Today, we're fixing this situation! Founders, if you intend to raise VC money, read on.

You will learn how VC firms actually make money - including some of their dirty tricks - and what it means for you as a founder.

Ready? Let's jump in.

Table of Contents

1. VCs are not the real money - LPs are

First-time founders are fascinated with VCs, this big bag of walking money.

But VCs don't invest their own money. Actually, they invest on the behalf of the “real” money: their LPs.

LPs are entities that manage large amounts of capital. Like, very large.

A typical VC fund has $100M-$1B under management, while your typical LP is 10x bigger.

There are 13 major types of LPs:

- Single Family Office (SFO) : Manages the wealth of one ultra-high-net-worth family

- Multi Family Office (MFO) : Manages the wealth of multiple affluent families

- Fund of Funds (FoF) : A fund that raises from other LPs and invests in VC/PE funds.

- Pension Fund : Manages retirement savings for workers.

- Foundations: Invests donations

- Endowment/Trusts : Invests university funds or legacy wealth

- Sovereign Fund : Government fund investing trade surplus, oil & gas surplus…

- Corporates : Companies investing in VC funds from their profits

- Banks/Insurances : Invests capital from premiums, deposits…

- Development Finance Institution : Public-backed investor focused on development.

- Wealth managers: Private banking desks allocating the capital of their clients

- Retail platforms : Platforms aggregating capital from many HNWI

- HNWI: High-net worth individuals investing directly from their own checkbooks

When Sequoia Capital or Andreessen Horowitz invests $10M in a seed round, they actually invest the money of those LPs listed above.

But I know what all of you founders are thinking right now:

“Why don't I just cut the middleman and go raise directly from the LPs?”

For one thing, these LPs are incredibly difficult to access. Getting a VC meeting is a piece of cake in comparison.

For another thing, these LPs manage too much money to care about your $2M pre-seed. It’s impossible for them to allocate the necessary time to diligence your company in addition to all the other investment instruments that they are managing (fixed income, foreign exchange, public equities, etc.)

That's why LPs rely on VCs: they put 5% of their assets in a few VC funds, and trust them to do the groundwork of sourcing, screening, investing, and managing each startup on their behalf.

Case in point, here's how much each type of LP invests in the VC asset class:

LPs are where VCs get their capital from. Now, let's look at how VCs actually make money.

2. VC firms get paid following the 2/20 model

VCs provide a service to LPs by investing their capital.

In return, they get compensated following a model known as the “2/20”:

- 2% management fee. Every year, the VC charges 2% of the assets under management to the LP. This covers the fund's operating expenses.

- 20% carried interest. The VC keeps 20% of the profits on the fund after having returned the initial capital to the LP.

Not clear? Let's take an example: a $100M VC fund with a 10 year lifespan.

- Every year, the fund takes 2% from the $100M i.e. $2M per year to pay for the salaries, but also rent, software, accounting, legal... That's $20M over 10 years in fees to “keep the lights on”, regardless of performance.

- If the fund is successful , the LPs recover their $100M first (“return of capital”), plus 80% of profits after that. The VC firm gets to keep the other 20% of profit after return of capital and split it across partners. That's the carried interest, or “carry”.

As you can see, the carry is the real incentive here.

The carry aligns LP and VC interests: most VCs would get $0 in carry, since most funds actually lose money. But a successful $100M VC fund would get $20M in carry for a 2x return, $40M for a 3x return, or even $80M for a 5x return!

In theory, the 2/20 is a reasonable model. It reconciles short-term need for operating cash and long-term alignment of interests.

We'll see later that it's not always the case. 💀

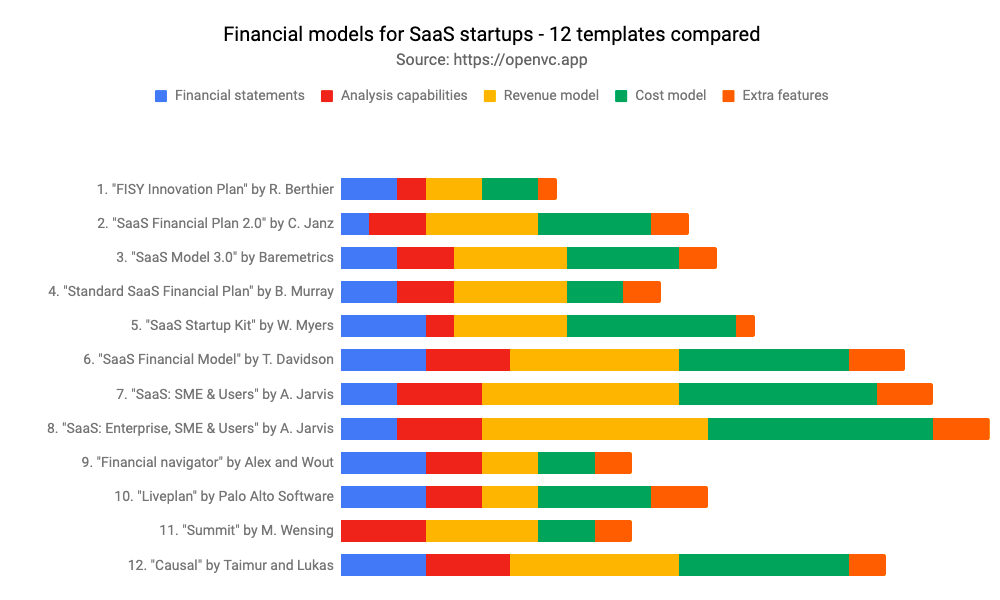

3. Simulating VC outcomes: 12 scenarios

The best way to understand a model is to run it, so let's do it.

First, let's three fund sizes: a micro-fund ($25M AUM), a medium fund ($250M AUM), and a mega fund ($2.5B AUM).

Then, let's three levels of net returns: 1x, 2.5x, and 4x. A 1x return is what your average VC gets, and it's bad. 2.5x puts you in the top 25% of all VC funds, and would likely allow you to stay in business. 4x is a great performance, and places in the top 5% of all VCs.

Finally, we can see our 12 scenarios at play.

Here's what it means for the medium fund of $250M:

- $50M in management fees over 10 years. That's $5M per year to pay for salaries, rent, legal, etc. For reference, VC partners in the US typically make $350k per year in base + bonus (source 1, source 2). Comfortable, but nothing crazy for a finance job in a HCOL area. A Google L5 engineer makes more. 🤡

- $0 in carry on average. Indeed, 50% of funds get a 1x return or less - they are as good as dead. You have to be in the top 25% to start making serious money and stay in business.

Our medium fund seems to be doing ok. Now, let's look at the extremes.

4. The 2/20 model breaks at the extremes

Management fees scale linearly with AUM.

The bigger the fund, the bigger the fees.

$10M fund → $200k/yr in fees. 😥

$100M fund → $2M/yr in fees.

$1B fund → $20M/yr in fees.

$10B fund → $200M/yr in fees! 😮

Arguably, small funds don't get enough fees and mega funds get too much.

Looking back to our 12 scenarios, a $25M micro-fund has to run operations on $500k/year. That's not enough. VCs really don't break even until around $50m in AUM. Vendors, software, etc. are all expensive.

The funds under $100M are typically new VCs, also known as “emerging managers”. If you think VCs are rich, think again - these emerging managers are pretty deep in it with their own pocket. Some take considerable personal risk and are much closer to founders in that regard.

What's more, those new VCs rarely get 2/20. Because they are unproven, they will often only get 1.5% fees and 15% carry… which means less money to pay for stuff.

The 2/20 model effectively acts as a barrier to the entry of newer, lesser wealthy VCs.

On the other hand, mega funds pull $10M+ in fees every year.

Does that really make sense? Does a $1B fund really costs 10x to run more than a $100M fund? When you make a guaranteed $100M per year, does your carry still matter?

To add insult to injury, those more established funds can negotiate better terms with their LPs. 2.5% management fees and 25% carry is not unheard of.

There is a structural incentive for VCs to grow their AUM just to collect more fees, a practice known as “fee farming”. In turn, valuations get inflated too, and this distorts the ecosystem as a whole.

This begs the question: how exactly do you grow a massive VC fund? Why doesn't everybody just start a big fund and farm the fees?

That's what we're going to see now.

5. Fund stacking - the 8th wonder of the VC world

VCs don't just launch one fund and stop there.

Quite the opposite. The whole VC business is about launching multiple funds successively, using the success of fund N to raise a bigger fund N+1.

That's why a VC firm (for example, “Index Ventures”) has multiple VC funds : Index V, Index VI, Index VII, etc. Each fund has its own start date, end date, and performance metrics.

If fund V performs well, the LPs will double down in fund VI, and new LPs will join in. Same with Fund VI. Same with Fund VII.

It's the circle of VC life.

However, if your fund performs poorly, things get tricky.

For emerging managers, that's likely a death sentence. LPs won't invest in your Fund II, period.

For established funds, you are allowed to have a bad vintage. LPs won't scorn you for having one bad fund, and want to maintain the relationship. Have two bad funds in a row, though, and they are going to have a harder time justifying you in their portfolio. Such is the VC game.

Oh, and did I mention? Compensation stacks up as well.

While you're running Fund V, you're still collecting fees and carry from Fund IV and III.

Noice!

At this point, you understand how VCs make money: they raise successive funds with bigger and bigger AUM.

You start with a meager $25M Fund I, you struggle, and if you're good, you end up with a $500M Fund VI fifteen years later, stacking up fees & carry across multiple funds.

All you have to do is consistently deliver good returns for your LPs.

Yeah, about that...

6. LPs expect 20% IRR and 2.5x net returns from VCs

Let's go back to the LP side.

Imagine that you're a LP - more specifically the head of a family office.

You are tasked with managing $2B for your favorite billionaire.

Your first reflex is diversification. You do some stocks. You do some real estate. You do some bonds. All classic stuff.

Then comes the time to look at venture capital:

- Your cash is locked in for the next 10 years.

- You have to figure out which VCs are actually good - and very few are, since most VC firms actually LOSE money.

- Bonus point: you have the privilege of paying 2% management fee AND 20% carried interest for that “service”.

Ugly stuff.

So here's the catch: to compensate for illiquidity, risk, and long holding periods, LPs expect at least 20% IRR - versus 10% with the S&P 500.

(I'll do a separate post on VC performance metrics - TVPI, DPI…- later. For now, let's just say this is a 2.5x net return.)

This is not easy to achieve. Data shows that most VC funds underperform the S&P500.

These two numbers - 20% IRR, 2.5% TVPI - will drive the whole conversation between LPs and VCs investments. And they will impact how VCs invest in startups.

This is the part where founders need to pay attention.

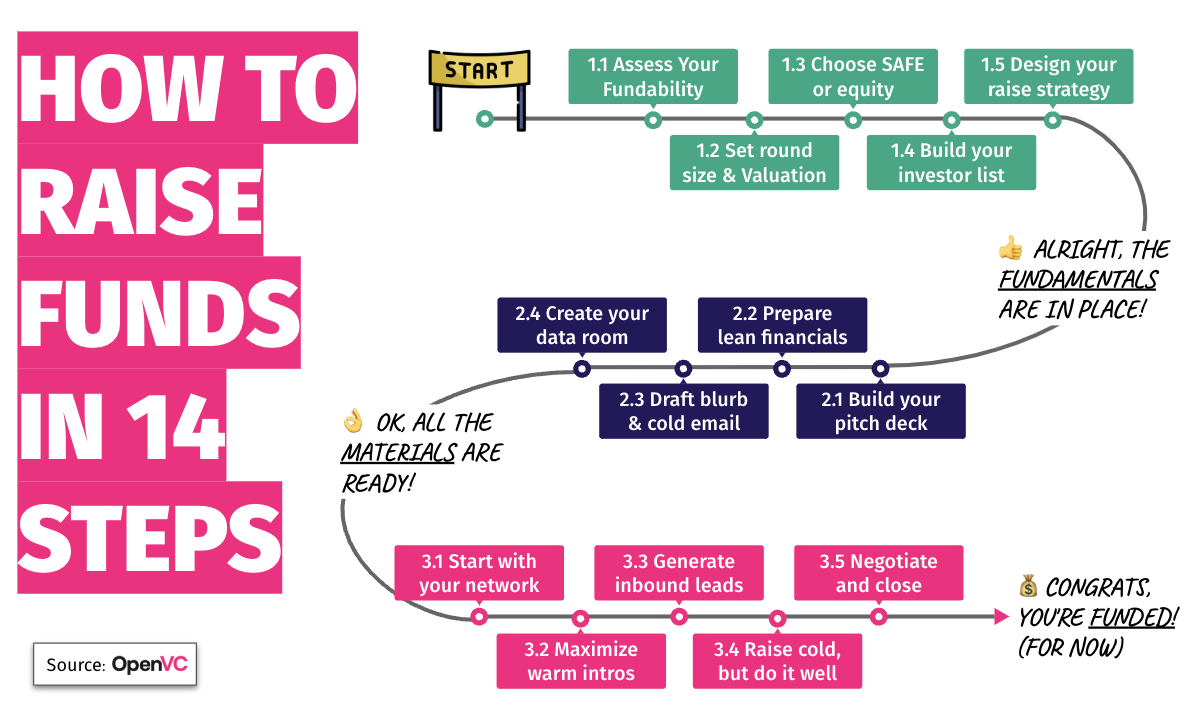

7. How LP targets impact your startup fundraising

Time for a bit of “VC maths”!

You're a VC. You just raised a $250M seed fund. Your LP wants a 2.5x net return.

Since startups are very risky, you invest in a bunch of them. Most startups will fail but that's ok, because a few will be huge winners and that's how you win.

This concept called the “Power Law” has been criticized, but remains the foundation of today's venture capital. It is baked into every fund model and portfolio construction.

Out of your $250M fund, $50M will go to management fees, leaving $200M to invest.

Assuming you cut 80 checks of $2.5M each, here's what you're hoping for:

As you can see, that single Home Run is magic! It returns as much as all 7 outliers, or as much as the 73 other startups combined!

That's why VCs are obsessed with companies that can return 10x-100x on a seed check.

They are not interested in a 5x return that would satisfy “normal people”. No, they would rather ‘100x or nothing”, because that's how the math works for them.

However, returning 100x is not normal. Only a small subset of companies have the profile to do that.

And that's how you get modern Venture Capital:

- They love software, because it's capital efficient = higher scalability, lower dilution.

- They favor large markets (SAM >$1B), because you can't build a billion-dollar company in a million-dollar market

- They chase fast growth (2x-3x YoY) because they are on the clock to return LP money.

As Sahith Aula from Katha VC summarized: “There are many incredible businesses out there, but most simply aren't VC backable. A VC backable business has rocketship growth, is defensible and sustainable, and addresses a high value market need. You have to hit all three!”

I'm not saying that in a jaded, toxic way, but founders need to understand this:

What your startup does matters, sure. But at the end of the day, it's not about your mission, your vision, or the problem you solve. It's about the ability for the VC to return his LP money and raise the next fund.

Everything else - team, market, competition, traction… - is predicated on that single core assumption.

Conclusion: Your startup is a financial product in the VC market

Fundraising is sales, you've heard that before.

But did you really think it through?

As a founder, you have two products: (a) the technology product that you sell to customers, and (b) the equity product that sell to VCs.

When you're raising, you're selling your equity on the VC market at a given price (valuation) depending on supply and demand.

In that sales process, the VCs aren't the “end user”. Instead, your equity is packaged into another product, the “fund”, and sold to the LPs (not an accurate description, but you get the idea).

The LPs are the ones who ultimately consume the value created by your equity product. The VCs, as intermediaries, just grab a slice of that value.

If you want to raise i.e. sell your equity, you have to deliver the right value prop: the ability to 100x the check of your VCs, so they can 3x the check of their LPs.

That's what they think about when they look at your deck.

And now, you know.

Bonus: 8 VC tricks to make (even more) money

The 2/20 is the core model of VCs, but of course, there are some shenanigans happening on the side.

Trick #1: Recycling fees

Out of a $250M fund, $50M are supposed to go to management fees. That's a lot of money! Instead, some VCs invest part of the management fees into portfolio companies. This is a good way to boost capital efficiency and shows alignment with your LPs.

Union Square Ventures has been fairly vocal on the topic.

Trick #2: Opportunity funds & SPV

As a VC, most of your startups will be failures. So how can you maximize the impact of your few home runs?

Answer: you raise a new fund or a SPV, just for your winners! This lets you double down on your best bets with new fees/carry.

A16Z showed the path in 2016 with their Growth Fund, and the industry followed suite.

Trick #3: Media Revenue

Content and events are important tools for VC firms. But some VCs are so good at it that they monetize them and create a separate revenue stream.

My favorite example is SaaStr Annual, the world's largest SaaS community event, which finds its roots in SaaS VC Jason Lemkin.

Trick #4: Direct Secondaries

If you invest at seed, you may have to wait 10+ years until you return money to their LPs. Alternatively, you could sell secondaries i.e. sell shares early to some later-stage investors. You make a lower profit, but you get liquidity earlier.

Excessive use may signal lack of confidence to LPs or founders, though, so use with caution.

Trick #5: Board Fees

Some VCs charge portfolio companies for their presence at the board. This practice is not seen super well in the US, and is more common in less mature VC markets e.g. Middle East or India.

Trick #6: Finder’s Fees

More generally, some VCs will try to sell services to their portfolio companies to generate extra income for themselves, for instance by taking a % of fundraising or M&A transactions that they facilitate.

This blurs the line between VC and banker, and is often frowned upon by institutional LPs.

(In the US, it also requires having a Series 7 or being a RIA. If not, then the whole company is at risk of a fun episode with the SEC.)

Trick #7: Owning or Referring Service Providers

Some VCs may refer their from portfolio companies to specific service providers (e.g. hiring, lawyers, accountants) and get a referral fee from that intro. In some cases, the VC may even OWN the service provider altogether!

This raises obvious conflict-of-interest concerns. Are you sure you want your VC doing your books?

Trick #8: Putting himself on the founder payroll

This one takes the cake.

The investor cuts a check, but in return, you must hire him for some obscure role at a determined rate.

I've only seen that myself done by angel investors (see below) but wouldn't be surprised to see it in less mature VC markets.

I don't know what you think of it, but IMHO, this belongs to our list of VC scams.