Jade Ruscev, Esq. is an attorney licensed in New York and Paris. She practices in both jurisdictions. Jade works a lot with international founders who want to open a business in the U.S. She is also a mentor in several accelerators and incubators, and many of her clients are YC startups. She sits on the Cornell Law School Alumni Board - that’s where she graduated from, along with the Sorbonne. Her specialty is corporate law: incorporations, fundraisings, equity grants, flips, and exits. You can reach out to Jade at staminalaw.net.

Read along or watch the full interview below!

Table of Contents

Watch the whole recording

When Should I Incorporate My Startup?

Usually, founders incorporate in the U.S. when they’re ready to actually run the business - meaning they need to sign contracts, invoice clients, or work with American partners, universities, or investors.

You also need a U.S. company if you’re joining a program like YC, because they only invest in U.S. entities.

And finally, if you already have a company abroad but want to raise money from U.S. venture funds, you’ll almost always need to create a U.S. parent company (“top-co”), because most VCs won’t invest directly in certain foreign entities.

I'm not American. Can I Incorporate a U.S. company?

Yes, you can. Foreign founders can own shares, be directors, and serve as officers in a U.S. corporation. You don’t need to live in the U.S. for that.

What you do need to check is immigration law. If you plan to physically work in the U.S. for extended periods, talk to an immigration attorney. Many of my clients live abroad and manage their U.S. companies remotely, which is perfectly fine.

Should I incorporate in Delaware like everyone says?

Recently, Elon Musk tweeted that SpaceX moved to Texas and that other companies should leave Delaware. This caused a lot of questions from the founders.

Despite what you see on Twitter, Delaware is still the gold standard for startups raising venture capital.

It’s not about taxes - you pay taxes where you operate, not where you incorporate. The advantage of Delaware is its legal system: it’s a common law state with decades of corporate case law and highly specialized judges. Things move fast and efficiently.

If you incorporate somewhere else, like Wyoming, and later convert to a Delaware C-Corp (which you’ll likely need to do), it can take much longer and cost more.

The annual Delaware franchise tax is small - usually under $1,000 for early-stage startups. So yes, Delaware remains the best choice for 99% of tech startups.

Should I incorporate as a C-Corp or an LLC?

Let’s talk about structure.

Some founders prefer LLCs, but investors always ask for Delaware C-Corps. You can’t realistically raise venture capital as an LLC.

An LLC is a pass-through entity for taxes if you don’t do an election. VC funds don’t want to deal with that, because it can trigger unrelated business taxable income for their LPs and create complex multi-jurisdictional filings.

It’s also hard to grant stock options in an LLC. With a C-Corp, you can easily issue common stock to founders and your team (whether directly or via stock options), and preferred stock to investors.

VCs expect a C-Corp structure, and they need it for tax benefits like QSBS (Qualified Small Business Stock). So unless you’re running a small consulting business, you should be a Delaware C-Corp from the start.

Don’t try to be creative with legal structure. Be “vanilla.” You want to innovate with your product, not with your incorporation.

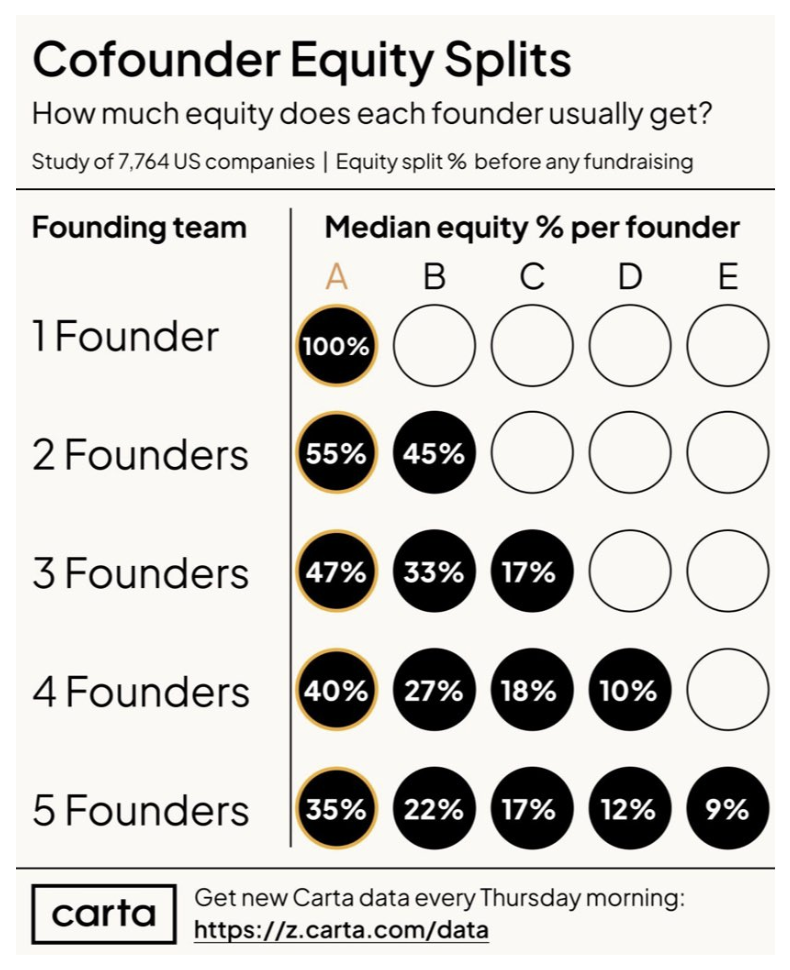

How do I Split Equity with my co-Founders?

When you incorporate, you file a Certificate of Incorporation with Delaware. That document lists your authorized common stock - usually between 10 and 11 million shares.

Authorized shares are not the same as issued shares; they’re the maximum the company can issue. At incorporation, typically 80% goes to founders and 20% is reserved for the stock option pool (for employees, advisors, and future hires) and/or a buffer.

The par value is extremely small - usually around $0.0001 or $0.00001 per share - so founders pay a few dollars total for their shares.

So founders buy their shares cheaply at par value. You want to keep the fair market value low to make future grants affordable for your advisors and employees.

What is “Vesting” and do I need one?

Vesting means you earn your shares over time. If you leave the company early, you don’t get to keep everything.

As a founder, you receive all your shares at incorporation, but when you leave the company, the vested shares can be kept (even though there is usually a negotiation with the company for a repurchase at FMV) and the unvested shares are repurchased and cancelled by the company.

The standard vesting schedule for startups is 4 years with a 1-year cliff , vesting monthly thereafter.

So if you leave before one year, you get nothing. After one year, you start vesting monthly until year four. It protects everyone: founders, investors, and the company.

Vesting is basically the “divorce clause” between co-founders. Without vesting, if your co-founder leaves after two months, they could still own 50% of the company - a disaster for future fundraising.

So yes, you absolutely need a vesting clause.

By the way, the standard vesting is 4 years, but there's a trend for requests of longer vesting (6 to 10 years) due to the fact that exits take much longer to happen today than in the past.

While it makes sense in theory, it doesn't do much in reality because your vesting will likely reset at some point within the first 4 years.

Wait, what do you mean “my vesting will reset”?!

Often at the first priced round, investors will “reset” founder vesting for another four years starting from the closing date.

It can feel frustrating for founders, but it's a normal part of the process. It’s a way to ensure founders stay committed after fundraising. Sometimes only part of the equity resets, depending on negotiations.

What about the acceleration clause?

The “acceleration clause” allows your vesting to accelerate in certain situations, usually a change of control (for example the company is acquir ed).

- Single trigger: All shares vest upon change of control

- Double trigger: Shares vest upon change of control and you are terminated within a certain period of time before or afterward.

It’s a protection mechanism, especially during acquisitions when teams are often restructured.

That way, you are sure to get all your shares if your company gets sold earlier than expected and you get fired. Double trigger is most common than single trigger.

How does vesting work if I want to fire my co-founder?

If the relationship breaks down, you first remove your cofounder as a director and officer. That stops their vesting. Then, according to the vesting clause, the company buys back their unvested shares at par value.

However, you may also want to buy back their vested shares!

Even if it's only 5%, having dead equity on the cap table may still be a problem. For vested shares, you usually negotiate a buyback at fair market value and have them sign a waiver of claims (they agree not to sue the company and its stockholders) in exchange for a severance amount.

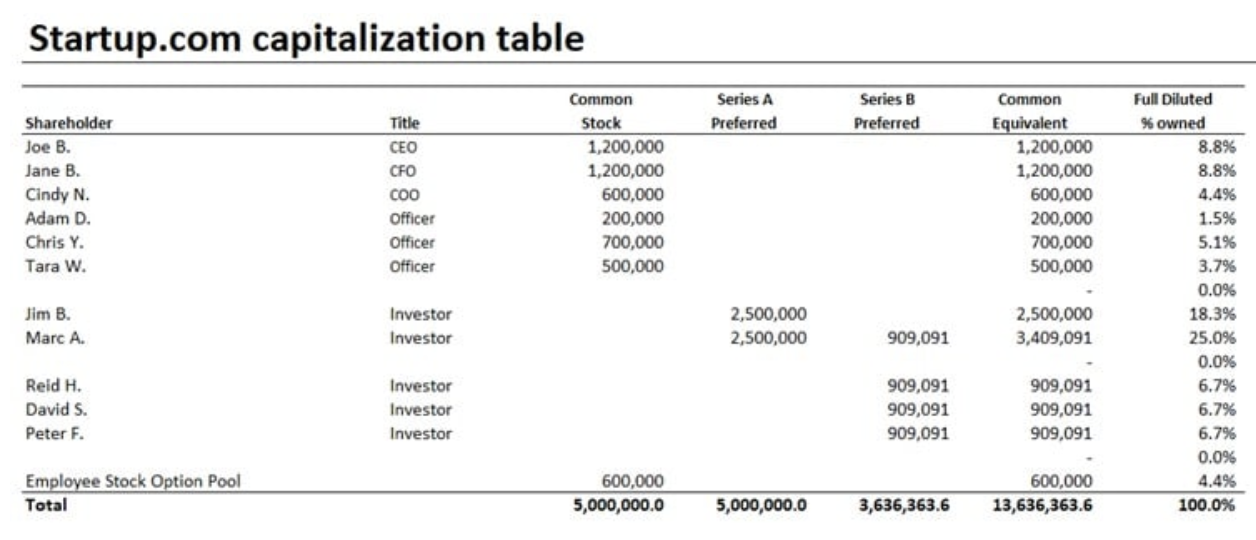

What is a cap table exactly?

Your cap table shows who owns what — founders, employees, investors, advisors.

Founders and employees end up with common stock ; investors end up with preferred stock (Series A, Series B, etc.).

You’ll see both non-fully diluted (current) and fully diluted (including all potential options and other instruments giving rights to shares exercised). Investors usually look at the fully diluted numbers.

Understanding how these ownership structures tie into your broader fundraising terms and legal setup is essential — especially as you navigate the legal basics of startup fundraising.

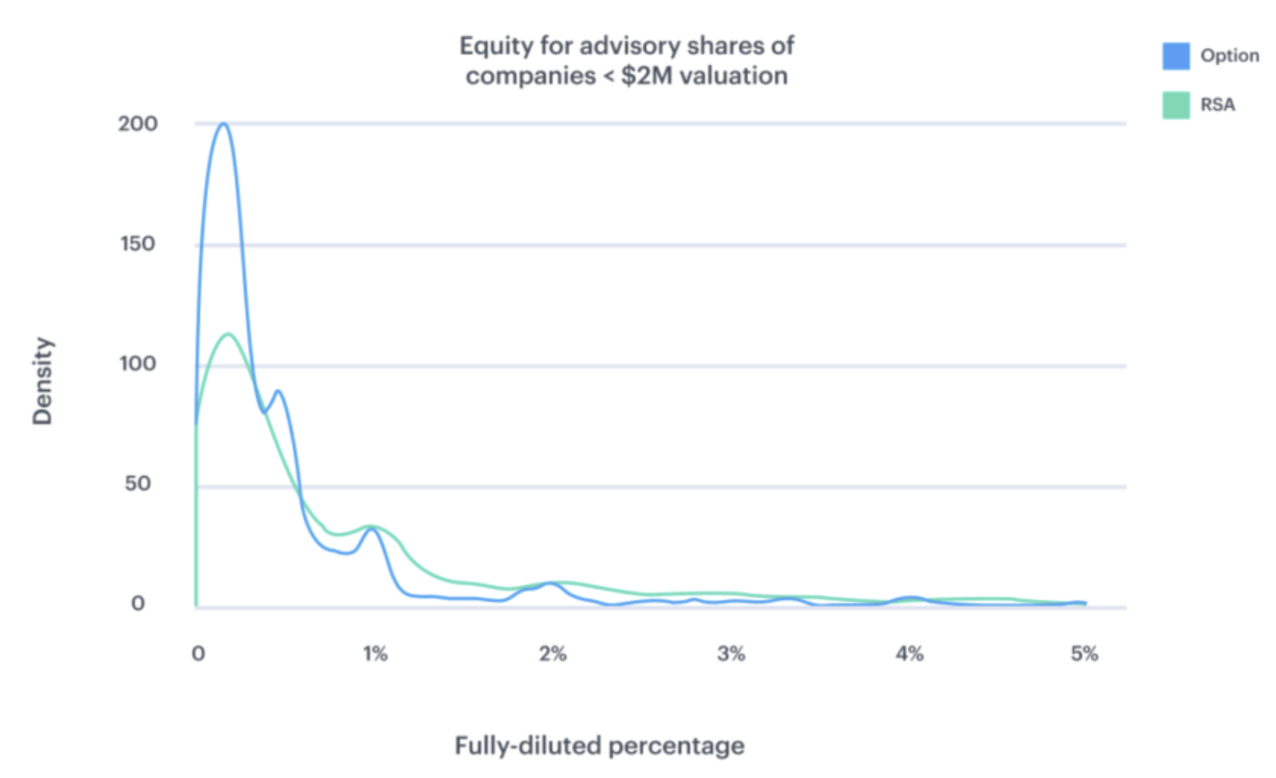

Should I give equity to advisors?

Yes, it’s common when you can’t pay cash. Typical range is 0.25% to 2% , depending on contribution.

But don’t give too much! VCs want the founding team to retain control and motivation.

Your option pool (usually ~10% at incorporation) should cover advisors and employees until the next funding round.

For more details, check out our post on advisory shares.

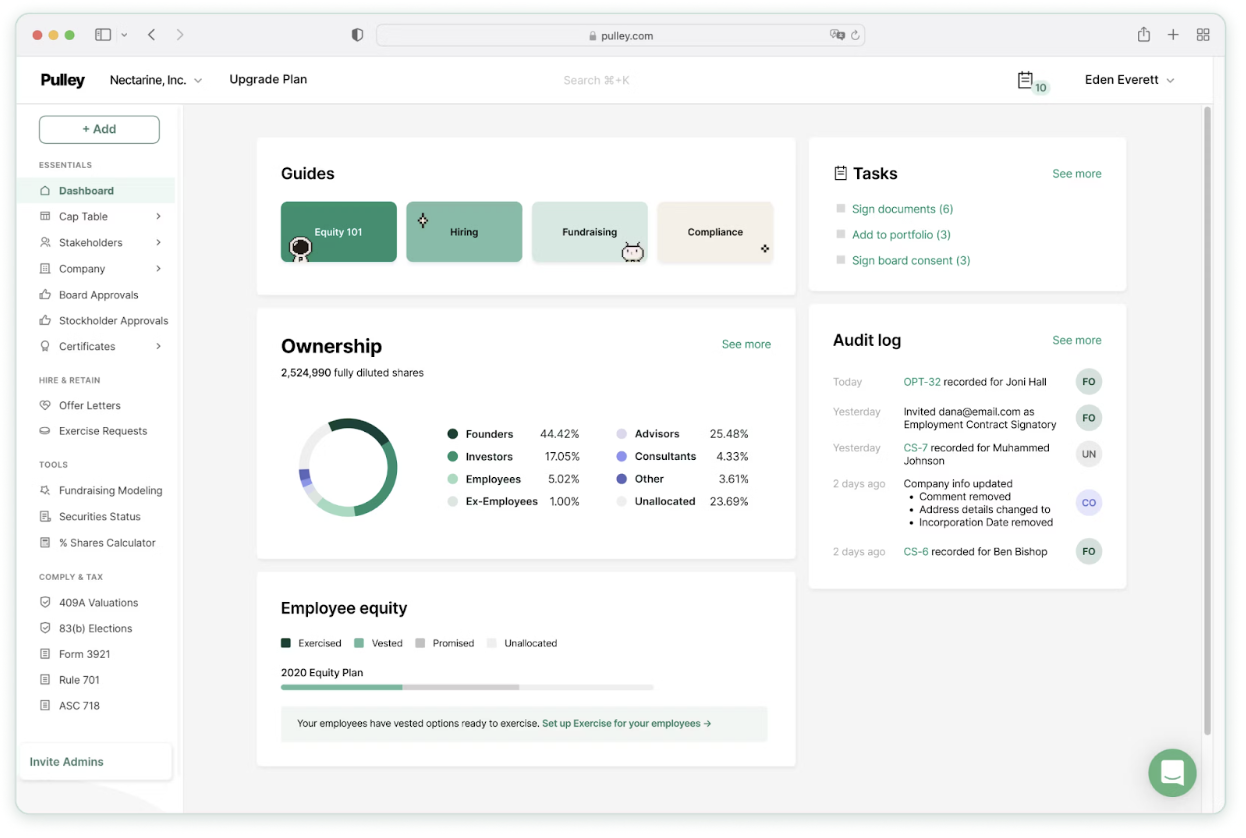

What tool should I use to manage my cap table?

In the U.S., Carta and Pulley are the most popular. They let you issue stock, track vesting, and simulate fundraising dilution easily. They’re also what most investors use.

What should I do with my IP (brand, patent code, logo) at incorporation?

Every person developing IP - founders, advisors, contractors - must sign an IP assignment agreement transferring ownership to the company.

If they don’t, the company doesn’t legally own its core product.

For health-tech startups working with universities, it’s different: usually the university owns the IP and licenses it to the startup.

How much does it cost to incorporate my startup?

You have two main options to incorporate:

- Use a platform like Clerky or Stripe Atlas ($500–$700).

- Work with an attorney ($2,500–$5,000).

Some founders combine both - using a platform for setup and a lawyer for questions. That way, you get the critical advice you need while keeping costs low.

You’ll also pay:

- Registered agent: ~$200–300/year

- Business address: a few hundred per year

- Delaware filing fee: ~$300

- Miscellaneous mailing fees: a few dollars

Lawyers often charge $350–500/hour if you go hourly, so fixed-fee packages are better.