Ulric and Rémy are the co-founders of Vauban.io, an online platform that helps investors create their online funds to invest in startups. After a meteoric success in recent years, Vauban has just been acquired by Carta, the American heavyweight of the sector. An exceptional exit for the two friends from the South of France, who agreed to be interviewed by OpenVC for 1 hour. An exclusive piece of content that we are delighted to share with you.

Steph: Ulric, Rémy, hello and thank you for coming to do your "exit interview" with OpenVC. The principle is simple: we talk about your entrepreneurial adventure, for one hour and without any fluff, from the beginning of Vauban to your acquisition by Carta. The goal is to go beyond the press releases and really understand the secret sauce of your success in order to educate and inspire future entrepreneurs. Is that okay with you?

Rémy & Ulric: Okay great.

Steph: To start, here's an image. Can you comment on it?

Rémy: Ah, this is the OG, our old website! And again, this was pretty advanced, we already understood some of the industry lingo.

Ulric: The oldest one came before when we were called citadelle.io. By the way, a little anecdote: there's a very famous hedge fund called Citadel Securities, Kenneth Griffin's fund, and they sent us a cease and desist letter to stop using the name Citadelle. So after three months, we had to change the name to Vauban, the engineer of Louis XIV who created all the citadels in France. We took it as a challenge: "You want to be a citadel, we're going to be the guy who creates all the citadels."

Steph: And even before Citadelle, there were other things, right? Tell us about how you first met and your first collaborations...

"We thought - Why not us? We want to be bought out for 20 billion too!"

Ulric: We met in business school at ESCA Angers, in our first year. We liked Forex trading on eToro. So for our first project, we said we would try to hack the market, to make algorithms to trade, etc…We spent a year doing that. We lost our pocket money but we enjoyed working together, it was a bonding experience. At that time, WhatsApp had been bought by Facebook for 20 billion. We thought, "Why not us? We want to be bought out for 20 billion too!".

Ulric: At the time, in 2012-2013, it was trendy to launch iPhone apps, so we thought that's what we'd do. Our first app was an app to save your SMS and then print a book of your SMS, called Save SMS. We did that for six months, but it didn't work very well. Then we changed our project, and for two years we worked on a fashion Tinder, where you can swipe a lot of clothes and decide to buy or not, and see what your friends thought of the clothes. It was a bit weird because we had no affinity with fashion. We didn't know anything about fashion. We never talked to our users, who were mostly women. We had never talked to a potential user. We spent two months deciding on the color of the logo and the name. We made all the stupid mistakes that people make in their first venture, you know. And those are mistakes that we don't make anymore. Today, we take a name, a logo, a landing page, and we go. But it's true that when you're starting out, I have the impression that it's quite common to spend time on details like that.

Steph: When did you start working on Vauban? There's often a fuzzy period where the project slowly emerges... How long did it take between the idea and the incorporation in your case?

Rémy : About a month. Maybe we would have waited longer in France, but in the UK, incorporating is really, really simple, and it costs 10 pounds. So between the brainstorming, the landing page and the incorporation, it was about a month.

Ulric: As soon as we did the landing page, we put Google AdWords on it and we immediately got calls from extremely qualified people. They were asking us, "we want a commercial proposal" or "we want an invoice". So we had to have a company.

Steph: Indeed, we often say that we incorporate either to raise funds or to invoice customers. In your case, it was case number two?

Rémy: Yes, exactly.

"The truth is that we did a lot of manual work in the beginning."

Steph: You wanted to invoice customers, but did you already have a product at that time?

Rémy: Not really, no. The truth is that we did a lot of manual work in the beginning. People were still happy, we did everything very well, but "by hand." I would say we had an MVP after not that long. How long would you say? Three months, not even, two and a half months.

Ulric: The funny thing about structuring a fund is that it's very structured: first, you have to go through compliance, then you have to do the legal paperwork, then you have to onboard your investors, etc. So for the MVP, we added a lot of work to the process. So for the MVP, we added tabs as we went along, each time the clients went through the process or if they asked for something. The first tab was to do compliance, then the second tab was to generate legal documents, the third tab was to manage your investors, and we were tracking the process.

Steph: You digitized an administrative workflow, step by step.

Ulric: By itself, the whole workflow could be done manually, that's what got us started.

Steph: Ulric, you have a technical background in computer science. Did you code the MVP?

Ulric: Yes, that's right.

Steph: Okay, so you didn't need to find a CTO, for example, at least not in the beginning?

Ulric: No, not at first.

Steph: So why did you raise money? What was the need?

Rémy: To scale. When we first raised funds, we had four or five clients and 130,000€ in sales, so it was really pre-seed, it was very, very early. You have to understand one thing: our business is this kind of thing that is very easy to do superficially, but there is really a depth, an infinite complexity in each of the elements if you want to do it right. What we were doing in the beginning was purely manual. We really needed to hire a team of engineers to build a product with more depth on each axis. However, our product-market fit was really, really, really strong. From the very first landing page, we had a lot of people interested, a lot of highly qualified people saying "this is really great". At the beginning, I was taking most of the client calls because Ulric was working on the MVP and that kept me busy all week. And that was on a marketing budget of 200 or 300 bucks a month, which was really minimal. The product-market fit was really strong, we were really happy: we had found a little treasure. Later, we understood why nobody had done it: because in fact, it's very, very, very, very hard to execute. So at the time we were raising, if I remember correctly, there was no "we're going to hire sales, marketers, etc." on our deck, because there were already over 100 leads in the pipe. That was more than enough to get to seed. The challenge was really the technical execution of the promise we were making.

"Honestly, we really had a lot of fun during the first 2 or 3 years, which were extremely hard, when we had to work 80 to 90 hours a week."

Steph: During that period, how did you personally survive, since you were full time on Vauban? Was the turnover enough to pay you?

Rémy: In the first six months before the preseed, we had no salary. I had worked a year before, we had both bought cryptos, and earned a little money that way. Not hundreds of thousands, not huge amounts, but enough to prime the pump and pay our rent for six months.

Steph: You just had six months of runway as an individual? I ask because we really have a lot of questions about that. Do founders wonder if it's the angel's role to pay their rent or do you have to have already demonstrated something with your own cash?

Ulric: Already, in Vauban, we put in 3,000 pounds each to start the company. After that, we were lucky: our first invoice was 70,000 pounds payable over a year, so we collected 20,000 pounds for the first quarter. We were lucky to be in an industry where it's big bills. That allowed us to hire someone after two months. Our personal runway was maybe six months, something like that.

Steph: Were there times when you were shaking or were you serene throughout that period?

Ulric: You take risks, but it's not the war in Afghanistan either. At worst, you go back to your parents after six months. Everything was relatively calm, we weren't in a total panic, but we gave it our all to avoid that. We had a joke: we didn't want to "go back to the pool in Aix-en-Provence" at our parents' house, where we spent all our summers with Rémy brainstorming ideas for start-ups.

Steph: Right.

Rémy: It's absolutely true what Ulric says. That's what I tell all the people who really want to embark on the great entrepreneurial adventure: the risk is overrated. Starting a business is risky, you're bound to lose some money and time. But for most people, a failure is absorbable. Of course, there are unfortunately people who can't afford it, but it's rare. At worst, we told ourselves that we could always go back to our parents' house and apply for jobs from there. We told ourselves that at worst, in six months, we would have managed to get back to a more or less normal life. It's not such a big risk, really, compared to what it can bring from a financial point of view, obviously, but also from a personal point of view, in terms of happiness and development.

Ulric: Honestly, we really had a lot of fun during the first two or three years, which were extremely hard, when we had to work 80 to 90 hours a week. That was when we had the most fun. We had a lot of laughs, we had a lot of fun, really.

Steph: Did you work together in the same place or were you remote?

Ulric: No, no, we lived together and worked together.

Steph: Do you think this phase can be done remotely?

Rémy: It's not as much fun... Maybe it can be done. I imagine that for people who have a family, it can be more complicated to do this aspect in person. So I guess it's possible, but it's still more difficult.

Steph: So, you don’t have children, neither of you have?

Both: No.

Steph: How old are you?

Both: 28.

"Today, Paris has become almost equivalent to London in terms of fundraising."

Steph: Okay. And so why London? Was it a strategic choice? Was it just random?

Rémy: That's a question we get asked all the time. I was in London at the time, so I guess it was a bit of a factor, because it was a place I knew a little bit, where I had met some people. Then we went through our options. First, there was the option of doing it in the South of France, because our parents were there, so we didn't have to pay rent. But it's pretty rare that people manage to create startups that scale and raise money outside of a major economic area. Then there was Paris, but it's a little less strategic for our business, which is a very Anglo-Saxon thing, where it's common law and very much linked to finance. On the other hand, we obviously speak the language much better. And, we didn't necessarily know many investors, we didn't know anyone, in fact. We were foreigners just as much in Paris as we were in London.

Ulric: What I liked about it was that it was a bit outside of our comfort zone. Like, I arrived in London with my coffee machine in the middle of February. I had asked Remy, "What's the weather like in London?" He said, "Don't worry, it's very mild.” There was a snowstorm for three weeks, something never seen before in London!

Rémy: It was Paris-Moscow! It was this winter where it was extremely cold, and it was quite funny because we were looking for an apartment under the snow. It was fun, it was really fun. We looked for a place to work too, cafes to work in, it was really fun.

Steph: Today, for a European founder who would wonder where to base himself, should he choose London, Paris, or Berlin? Especially today with Brexit, how do you see it?

Ulric: Paris, four, five years ago, was not the European tech hub that it is today. Today, Paris has become almost equivalent to London in terms of fundraising. It's a place that has become very attractive. So I would say that it depends on the market. What I like about London is the international dimension. A lot of founders have the ambition to expand to the US or internationally, and it's true that in London, from day one, everyone has to speak English and you're only going to recruit people who can speak English. That makes it easier to expand internationally.

Rémy: If you take into account all the other variables, I think that London is a little bit better than the other European capitals, because it is a very, very international place. I think that more than a third of the population of London is of foreign origin. So, it allows you to have an international network and it's a bit easier to raise funds. I think it's also a little easier to get bought out. When American companies buy a company in Europe, there is always a little mistrust. This mistrust is always greater towards France than towards the UK, where the regulations and the system are more similar. However, that's not what makes a company successful, and you can be just as successful in London as in Paris.

"We took the difficult decision to separate ourselves from all our hedge fund clients. We lost 80% of our business right after we raised our Series A."

Steph: Another fascinating episode of your early years is the pivot. Can you tell us about it, Ulric?

Ulric: The rocket was taking off for the first three years. We started during the crypto-fund boom so everyone wanted a crypto-fund at the time. But we felt like there was something strategically wrong with it. One day, I sat down at a restaurant with Remy and realized that we were actually going down a dead end. It's very strategic, it's very related to the product and strategy, but let's say that what we were doing was replicating an investment structure that was institutional but for very small funds. We would incorporate a fund in the UK or offshore, in the Cayman Islands or in the US. It was a very heavy infrastructure, very technical for a small fund that could very well be launched in copy trading on eToro, on Interactive Broker or on Robinhood. So we thought that the people who were going to win this market were going to be brokers like eToro who were going to launch their offer where you could create your own small hedge fund. Replicating an institutional structure wasn't really working for our clients. So we took the difficult decision to separate ourselves from all our hedge fund clients. We lost 80% of our business right after we raised our Series A. From there, we focused entirely on private markets, starting with VC, because we had a little bit of traction, and it was the best decision of our lives. In one year, we grew 300%. Having lost 80% of our sales just before, we actually did ten times the growth just on the VC product. This was really a huge product-market fit. It was a very risky decision when we made it, and it really paid off.

Steph: Since we're on the retrospective, how would you judge your performance in hindsight? What did you do well, and what would you do differently if you had to do it again?

Rémy: What we did well was the corporate culture. We had a very, very clear idea of what we wanted in terms of culture, people who are passionate about our subject, who work very hard, who are very generalist, who manage to work on a lot of topics at once. We were also very attached to having an office culture. Except when it was during the heart of Covid, we always had an office policy. I think we did that very well. People were very proud to work at Vauban, very fulfilled in their work, and the "tribe" filter worked well, meaning that people who were not necessarily highly motivated by this kind of work atmosphere or by the subject we were working on left very quickly. A good culture is a binary culture: either people say "this is the best place I've ever worked" or they say "this is not for me" and they leave. When it's that binary, it's a sign of a really good culture.

Steph: You had grown to how many employees before the acquisition?

Rémy: 55.

Steph: Ulric, do you agree with the diagnosis?

Ulric: I agree with Rémy on the culture. The only downside is the recruitment. The culture was very strong and the people were very close-knit, but we had a 50% churn during the first two or three years. In all, we had to recruit 100 people and at the end, we were 55. I explain this because we didn't have a very... We didn't have a process at all, in fact! We didn't have a recruitment process. I would take a call with a candidate, I would say "Ah, damn, the guy is hot, Remy, do you want to talk to him?" Rémi was like "Yeah, I admit, he's hot. Come on, let's get him." And we did that for a long time. Then we hired Eric, our COO, and he got things in order. In the year and a half since he started, the churn is a normal 10% churn. But it's true that if we had to do it again, we would have to start with stricter recruitment processes.

Steph: At what point did you say to yourself, "Okay, this is working, we're good, we've got something."

Ulric: I think it was the landing page, when we were really getting dozens of requests via Google AdWords, we thought "Well bah, there's something to do here". We had launched 10 projects before, the Fashion Marketplace, Save SMS, and others, we had made landing pages, we had tested advertising on Facebook, on AdWords, etc. So we had a good sense of "what to do." So we had a good sense of "Is there something to be found in this product, in this industry or not?" And when we saw the conversion rate, we thought, "There's something to it."

"We had to do investment fund accounting. We learned that by buying accounting software and reading the documentation."

Rémy: If you scale the business between market risk and execution risk, we were really at the extreme execution risk. There was always demand, we had really found a niche where there was a need for a tool that people were begging us to produce. It's the execution that is really brutal and extremely difficult, a mix of finance, fees, taxes, tech, jurisdictions.

Steph: Can you give a small specific example to project on this complexity? Something that really hurt you to crack it?

Ulric: For example, we had no experience in law, and in particular investment fund law. We had to write legal documents, so we had to call on law firms to understand the documents, produce them and then automate them. Then we had to do investment fund accounting and we had no accounting experience, so we had to learn how to do it on the job. We learned that by buying accounting software and reading the documentation. Another trick: we would interview candidates and ask them, "If there was this problem, how would you handle it?" These were problems that we had for real with our clients that we wanted to solve. That, for example, took a long time, we struggled a lot with it because we were really starting from scratch in terms of experience. We had to work extremely hard to make up for this lack of experience in the industry.

Rémy: Afterwards, the need was so strong and the traditional competition was so bad, that it was not dramatic if the first product was cobbled together. It's not like launching a new email client, where it has to be impeccable, because there are plenty that work great and are free. In our case, there wasn't really any competition because fund administrators and lawyers deliver an absolutely abysmal customer experience in general. The bar was low.

"At some point, in start-ups, you have to land the plane, and we found that this was a good landing strip."

Steph: Now let's talk about the Carta acquisition. Rather than asking you questions, I want to get you to react to some comments found on social media. Some of them are nice, others a little less so, I'll let you read them. Remy, do you want to take the first one?

Rémy: Yeah, that's a comment we often hear whenever there's an acquisition in Europe, especially if it's an American group acquiring a European start-up. "It's a shame that nobody is building the next Apple or Amazon". It's true, it's a shame...

Ulric: Personally, this was our first real start-up. For us, the risk was too big to roll the dice again. Maybe in four years, it will crash and we will have lost everything, we will have lost ten years of our life. Conversely, if in five years we want to launch something else, we won't make an exit on our next start-up because we've already done it, so we'll want to go all the way, to the unicorn or the decacorn. At least, that's how we see things with Rémy. I have the impression that in Europe, we are at the first stage where people are making their first outing. The next generation, in ten years, will want to do something big because they will have done a release before.

Steph: Ulric, next comment.

Ulric: I totally agree with that. Yeah, we're young, it's a deal we couldn't refuse, both for our investors and for the employees, and for us as well. At some point, in start-ups, you have to land the plane, and we found that this was a good landing strip. We did a London - New York, nobody complained, there was some turbulence, but it went well. We could have gone to Mars, it's true, but everyone enjoyed the trip, and we don't want to crash.

Rémy: Let's just say that if the acquisition offer had come from a private equity group, we would have refused. But in this case, it was Carta, a company that we really admire. The project was very coherent and we knew that it was going to work out well. We knew that half the team would not be fired during the transaction, that everyone would be happy. Like Ulric says, it was definitely the right partner and the right time to land.

Steph: Okay, I understand. One last comment just to make you laugh. When I asked what questions to ask you, I was told that.

Ulric: Haha, I admit, we were honest, we didn't mince words. What I liked about Carta was their approach in terms of acquisition. I don't know if it's like that for all acquisitions, but they asked us what we wanted to do. They said, "Guys, we love what you're doing. Tell us, what's the project? Carta plus Vauban equals? What does it look like?" And it was up to us to define the integration project. It was very smart, because they didn't come with a specific project. They didn't come in and say, "Okay, we're buying you, we want to do this, this and this." It was up to us to create the project. They were very open.

"Carta is great for larger funds, and Vauban is specialized in smaller funds. The idea is to create a global platform to accompany VCs from their creation to their fund X."

Steph: Thanks Ulric, that makes a great transition for the last part: the future of VC tech. Today, the future of Vauban/Carta is in some ways the future of the entire industry. So what is the integration project? From a product perspective, are the platforms going to be integrated in the short term and become interoperable?

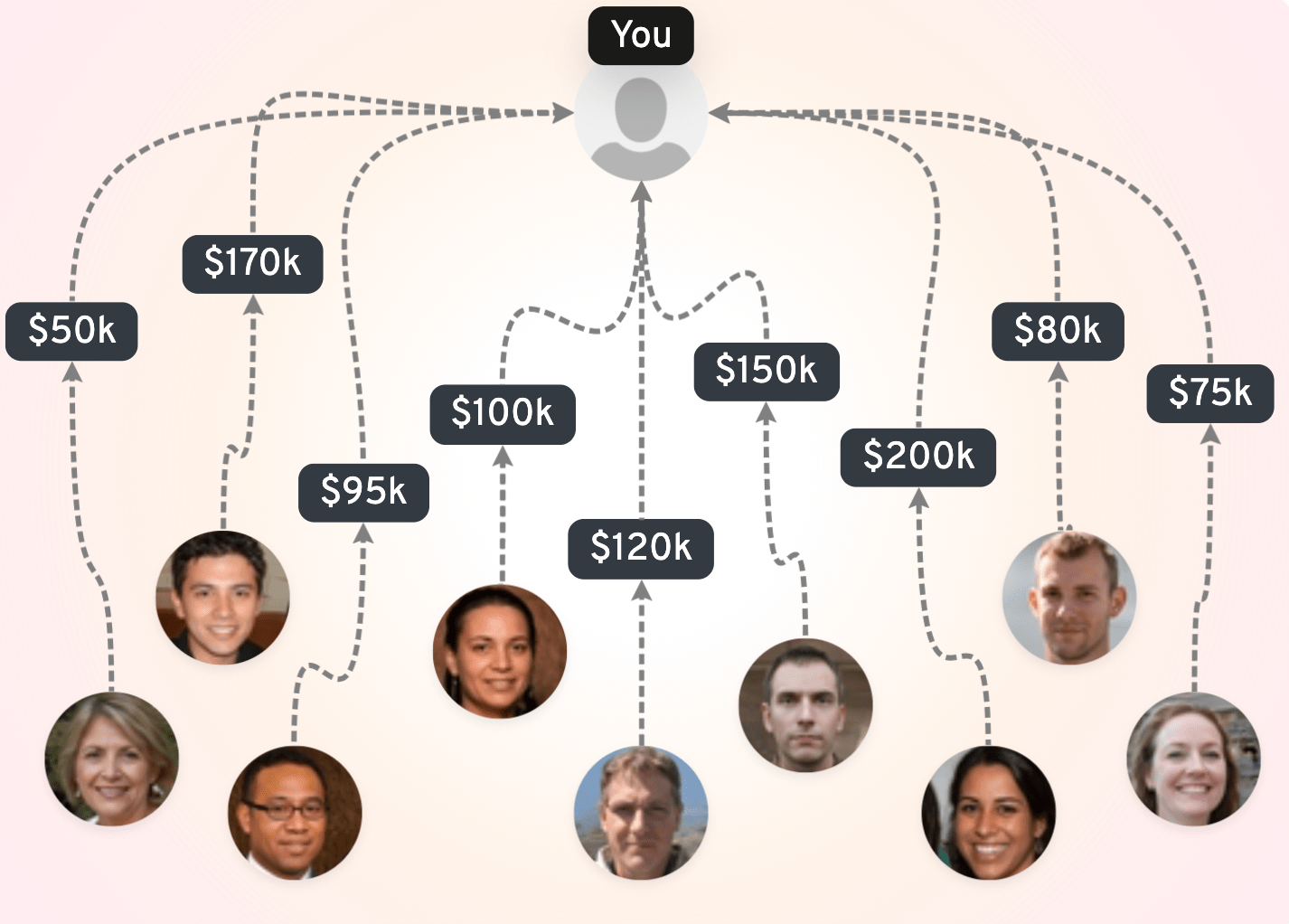

Ulric: Yes, that's the plan. Basically, we (Vauban) are very strong on the whole setup, i.e. the generation of legal documents, the creation of an SPV or a fund. And Carta is very strong on the administration and accounting part, because they created their own accounting system, which is very, very hard to do. That's one of the reasons why we sold: we didn't want to create that ourselves, it's very difficult. If you combine our platforms, you have the best of both worlds: a great setup on Vauban and an even better administration on Carta. The project is to combine these two strengths: to create a platform to start a $50K per SPV syndicate and to manage a 1 billion fund. Carta is great for larger funds, and we (Vauban) are specialized in SPVs and small funds. So the idea is to create a global platform to accompany VCs from their creation to their fund 10.

Steph: Is there also a challenge for you to differentiate yourself as a deal-as-a-service provider? We see a lot of companies appearing in this sector, particularly in Europe. What is the logic of the market?

Rémy: First of all, it's not a huge market, so you have to have global ambitions. If someone does the SPV provider in Lithuania, for example, it's not going to create a VC-able company that can make a huge exit or become the next Apple. You have to have the ambition to control a large geographic area, including the US. I think it's very hard to do a big business in this market without having the US. However, it's an interesting market because it's an infrastructure that allows you to go to other planets. There are a lot of things we can do to distribute products with high added value for investors, there are a lot of businesses to imagine. We can go vertically in depth and offer more things to these two audiences that are VCs and LPs, their investors.

"Bringing your LPs to AngelList would be like using Tinder's messaging feature to text your girlfriend on a daily basis."

Steph: If we talk about controlling the market, two players are clearly positioning themselves: AngelList and Carta. How do you see things evolving between the two?

Ulric: AngelList is very focused on Emerging Managers, which is when you start as a VC and do SPVs. The advantage is that they help you raise money for your first fund. The disadvantage is that when you are a VC and you bring your investors (LPs) on Angellist, your investors will be bombarded with investment proposals from lots of VCs on the platform. On the other hand, on Carta/Vauban, everything is very private: they will never send investment offers from your competitors to your investors. These are two very different models. Another concern with AngelList is that they have a hard time transforming. When you reach a certain size, 50 or 100 million in assets under management, you switch to Carta because you need more functionality in terms of accounting, reporting, you need to accommodate LPs that are more institutional, etc. The challenge for Vauban and Carta is to create a platform that can support you from start to finish. And that's how we want to play it.

Steph: So AngelList plays the community card, which gives them network effects at the risk of restricting themselves to emerging managers in need of funds. On the other hand, you offer a pure SaaS that covers the entire life cycle.

Ulric: Exactly.

Steph: That's very clear. Thank you very much, this is the first time I really understand Carta VS AngelLIst. Do you agree with that, Remy?

Rémy: Exactly. The disadvantage of the AngelList model is that it is marketplace-first. Therefore, it's hard to attract GPs who don't need the marketplace. They have no reason to expose their own investors to the platform. To make a bad metaphor, it would be like using Tinder's messaging feature to text your girlfriend on a daily basis. Of course, LPs on AngelList have access to all the opportunities of all the other GPs. Whereas if you're, quote, in a relationship, it's easier to use WhatsApp or Messenger, something private.

Steph: Last question: is the future a standard that allows all VCs and angels to invest across all platforms? Or will each platform try to take over all the deals?

Ulric: I think it's more like answer number two. Interoperability is a nice theoretical and intellectual concept, but in practice it is very complicated from an accounting, reporting, etc. point of view. Connecting all these platforms together would be like open banking for the private market. Maybe we'll get there, but it's a long way off.

Steph: I see. And what do you have in store in the short term?

Rémy: We've just launched our Atom product at $2K + 2% for angels to syndicate deals. We put quite a lot of work into it, and we want it to be the most cost-effective solution for investments under $200k in the UK and Europe.

Steph: Excellent, guys, thank you very much. I can't wait to see what you guys come out with in the next few months!

If you are an exited founder and want to share your story with OpenVC, email us at steph@openvc.app.

Find your ideal investors now 🚀

Browse 10,000+ investors, share your pitch deck, and manage replies - all for free.

Get Started